Why patient access to healthcare in Australia is so unfair

Independent Australia

24 Jul 2022, 12:22 GMT+10

The complex fragmentation of Australia's health system affects the availability of patient data to insurers and care providers, resulting in unfair payment distribution, writes Professor Francesco Paolucci and Josefa Henriquez.

HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS globally are under tremendous stress.

Demographic and epidemiological trends, healthcare costs and technological advancement, COVID-19 - and most recently global conflicts and their economic impacts - have amplified the need for structural sustainable solutions for healthcare financing systems worldwide.

According to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates, health spending as a percentage of GDP averages 8.8% across member countries - with Australia at 9.4%. Moreover, the relative importance of employment in the health and social care sectors is high and has experienced sustained growth since the 2000s, while still deemed insufficient to cope with increased demands for care.

Australia is no exception to these trends. Nevertheless, the country's current economic performance still allows health budgets to be wealthy.

Healthcare system forcing chronic pain sufferers to struggle

For instance, New South Wales received a record $30.2 billion for healthcare in 2021, representing a 9.2 % increase from the previous year's budget.

This is not the only intervention of this type. The newly elected Federal Government committed roughly $1 billion to Medicare in additional funding for primary care. No doubt, more resources will be much appreciated. Unfortunately, their effects are unlikely to be long-lasting.

Structural reforms to ensure sustainability

Healthcare financing sustainability is the fundamental issue to tackle - "one-off" boosts in funding do not have the intrinsic ability to address the structural problems afflicting access to performance and efficiency of Australia's healthcare system.

This is no surprise, as boosts are ultimately sporadic instruments, similar to their counterpart, "rationing" through budget cuts. Such rationing has led, in most national health or insurance systems such as those in England and Italy, to "death by austerity".

What are the key "structural issues" concretely affecting the long-term financial sustainability of the Australian healthcare system?

Three fundamental concerns are:

- fragmentation of funding and overlapping of governing jurisdictions;

- absence of integrated purchasing functions by third-party agents and derived lack of competition and choice of purchasers; and

- limited utilisation of prospective financing incentives and payment mechanisms, such as risk adjustment/risk equalisation.

Unintended consequences of current healthcare structures

Australia has a multitude of players involved in the funding of healthcare services: the Commonwealth Government, predominantly, subsidises access to general practice and primary care ($30.5 billion), as well as pharmaceuticals, public hospitals ($26.8 billion) and aged care ($23.6 billion).

State and territory governments manage and also finance public hospitals ($35.9 billion), and to some degree, primary health ($10.5 billion). Private health insurers fund around 8.2% of total healthcare spending and consumers contribute as much as up to 20% (and growing) in out-of-pocket contributions.

This picture self-explains two fundamental inefficiencies:

- the extreme fragmentation in funding - in the OECD only the U.S. shares this feature - with consequent lack of coordination in decision-making negatively impacting healthcare quality and equality in access to care; and

- the absence of integrated third-party purchasing entities to prudently guide and protect consumers in their healthcare journey.

Private insurance: Rising premiums and the truth behind it all

Ultimately the purchaser remains the individual, alone, who is assisted in the funding but not in the purchasing by a multitude of uncoordinated partial funders - none of which is wholly responsible or accountable for the quality of care delivered.

Most modern healthcare systems - for example, the UK, Netherlands and Germany - in the OECD have, since the 1990s, surpassed these passive funding structures and recognised the importance of active purchasing to mitigate the adverse consequences of asymmetric information between providers and consumers.

Some introduced choice of purchasers through commissioning and selective contracting to improve efficiency and performance in resource-constrained environments.

Several unintended but dire consequences derive from Australia's current healthcare structural issues.

Exacerbated partly by COVID-19, hospital waiting times have continued to rise in the public system. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) reports that those waiting more than one year for a total knee replacement jumped from 11% to 32% and for septoplasty, from 18% to 36%. This, by construction, disproportionately affects those with higher health needs.

While healthcare costs have been rising at higher rates than income and GDP, this has not been accompanied by adequate adjustments in Medicare fees, which in fact were frozen in an attempt to mitigate inflationary pressures.

This has resulted in de facto risk and cost-shifting being borne mostly by those in lower income and higher risks groups, compromising quality and fairness in healthcare access.

Potentially, this drives GPs to increase the number of patients they see to make up this money. Importantly, if individuals start facing higher out-of-pocket costs, it can defer access to much-needed care or lead to unnecessary emergency presentations. Indeed, reports suggest that about 400,000 Australians in 2020-21 delayed a visit to a GP due to the cost.

Time for long-lasting doable changes - where to start?

Australia's economy is in good standing to strengthen its healthcare system. Some much-wanted money is flowing for now due to global inflation, among other factors. The Government, therefore, has a unique opportunity to actively and strategically allocate resources to create conditions for incremental improvements to healthcare financing.

Here are some initial steps for change:

1. Clarifying roles through separation of purchasers and providers

This is long overdue. Coupled with enabling consumers' choice of third parties (such as the states, insurers, the Commonwealth Government or new trust-like entities) to proactively engage in contracting, such separation would surely enhance efficiency in the system - and likely quality and performance.

2. Introducing available (and globally tested) tools

For purchasers to act as prudent buyers of effective and fair healthcare, they need appropriate tools.

Concretely, one of the primary schemes used to manage the efficiency and fairness of healthcare spending is "risk adjustment". Broadly, this scheme, predicts healthcare spending among different risk factors in the population such as age, gender, or health status and prospectively distributes money to health purchasers or as a form of provider payment.

In terms of the risk adjustment/equalisation schemes, data is the primary constraint when designing feasible and effective models, as detailed individual-level information on spending - but also on risk factors - is needed.

Efforts should be made to develop integrated individual-level health data covering the full spectrum of healthcare services from primary to acute, all the way to aged care - independently of whether the contact is with public and/or private systems.

Although data integration and quality are paramount and pivotal to building effective financing models to attain productivity and efficiency gains, recent research shows that it's no excuse to have less than optimal or even very constrained access to good quality data.

In particular, recent empirical work offers a practical toolkit for reforming healthcare financing systems when data is constrained.

Essentially, academics with a focus on economic healthcare built a framework and tested it for competitive private health insurance markets. They found that the use of demographic information (age and gender) alone - which is readily publicly available in almost any healthcare system - coupled with ex-post risk-sharing performs and sophisticated data-intensive models, yields the same improvements in terms of incentives for fairness.

Marica Iommi et al similarly found (for national health services) that prospective models using readily available data and simple linear predictive modelling, perform at least as well as sophisticated artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI-ML) data-intensive models.

Hence, to improve our (and other) health systems, we may be "waiting for Godot", or, as some critics say, for a crisis to occur, while pragmatic changes likely to yield significant returns - for relatively little cost - are available right now.

Professor Francesco Paolucci is Professor of Health Economics & Policy at the Faculty of Business & Law, University of Newcastle and the School of Economics & Management, University of Bologna. You can follow Professor Paolucci on Twitter @dr_paolucci.

Josefa Henriquez is a PhD student at the University of Newcastle. Her research focuses on health economics topics.

Related Articles

Share

Share

Tweet

Tweet

Share

Share

Flip

Flip

Email

Email

Watch latest videos

Subscribe and Follow

Get a daily dose of Sydney Sun news through our daily email, its complimentary and keeps you fully up to date with world and business news as well.

News RELEASES

Publish news of your business, community or sports group, personnel appointments, major event and more by submitting a news release to Sydney Sun.

More InformationBusiness

SectionDollar General warns of slowing sales amid economic strain

GOODLETTSVILLE, Tennessee: Dollar General is bracing for a challenging year ahead, forecasting weaker-than-expected sales and profits...

Intel stock jumps 15% as Lip-Bu Tan named CEO

SANTA CLARA, California: Intel's stock soared nearly 15 percent this week following the announcement that former board member Lip-Bu...

UAW files labor complaint as Volkswagen cuts Tennessee production

DETROIT, Michigan: Volkswagen's decision to scale back production at its Chattanooga, Tennessee plant has sparked backlash from the...

Spotify paid a record $10 billion in music royalties in 2024

STOCKHOLM, Sweden: Spotify set a new milestone in 2024, paying out US$10 billion in royalties—the highest annual payout to the music...

Jaguar Land Rover opts out of EV production at Tata’s India plant

NEW DELHI, India: Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) has decided against manufacturing electric vehicles at Tata Motors' upcoming $1 billion factory...

Virgin Group aims to raise $900M for cross-channel rail venture

LONDON, U.K.: Virgin Group is seeking to raise $900 million to fund its plan to launch cross-channel rail services, positioning itself...

International

SectionTrump administration pushes food firms to drop artificial dyes

NEW YORK CITY, New York: The Trump administration is pressuring major food companies to remove artificial dyes from their products,...

Lawmakers debate military expansion amid European security fears

BERLIN, Germany: German Lawmakers are debating whether to loosen the country's strict borrowing rules to fund military expansion. ...

Trump to end U.S. government international news services

The Voice of America may not live up to its ambitious name for much longer. Michael Abramowitz, the director of VOA, said in a Facebook...

Dozens dead as U.S. launches large scale offensive in Yemen

WASHINGTON, DC - U.S. President Donald Trump has joined Israel's war on Yemen's Houthis, days after the group said it would resume...

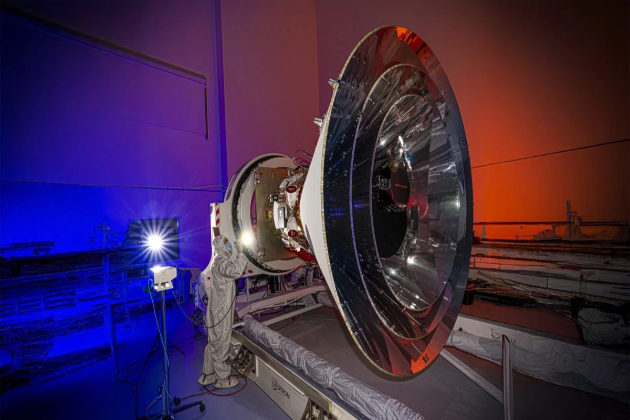

SPHEREx telescope to create a three-dimensional map of the cosmos

LOMPOC, California: NASA launched a new telescope into space this week to study the origins of the universe and search for hidden water...

Texas, New Mexico report 28 new measles cases in five days

AUSTIN/SANTA FE: Texas/New Mexico have reported 28 new measles cases in the past five days, bringing the total to 256 since the outbreak...